|

Symptoms

of malaria include fever and flu-like illness, including

shaking chills, headache, muscle aches, and tiredness. Nausea,

vomiting, and diarrhoea may also occur. Malaria may cause

anaemia and jaundice (yellow colouring of the skin and eyes)

because of the loss of red blood cells. Infection with one

type of malaria, P. falciparum, if not promptly treated, may

cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and

death. Symptoms

of malaria include fever and flu-like illness, including

shaking chills, headache, muscle aches, and tiredness. Nausea,

vomiting, and diarrhoea may also occur. Malaria may cause

anaemia and jaundice (yellow colouring of the skin and eyes)

because of the loss of red blood cells. Infection with one

type of malaria, P. falciparum, if not promptly treated, may

cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and

death.

For most people, symptoms begin 10 days to 4 weeks

after infection, although a person may feel ill as early as

8 days or up to 1 year later. Two kinds of malaria, P. vivax

and P. ovale, can relapse; some parasites can rest in the

liver for several months up to 4 years after a person is bitten

by an infected mosquito . When these parasites come out of

hibernation and begin invading red blood cells, the person

will become sick.

Any

traveller who becomes ill with a fever or flu-like illness

while travelling and up to one year after returning home should

immediately seek professional medical care. You should tell

your GP that you have been travelling in a malaria-risk area. Any

traveller who becomes ill with a fever or flu-like illness

while travelling and up to one year after returning home should

immediately seek professional medical care. You should tell

your GP that you have been travelling in a malaria-risk area.

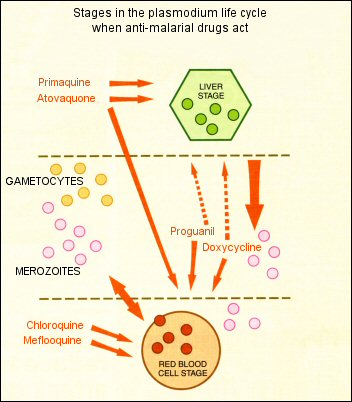

Malaria can be cured with prescription drugs. The type

of drugs and length of treatment depend on which kind of malaria

is diagnosed, where the patient was infected, the age of the

patient, and how severely ill the patient was at start of

treatment.

Anybody travelling to an area where malaria is endemic

is at risk of catching the disease. Lately there has been

an increase in the cases of malaria reported in the UK - in

1993 there were 1922 reported cases in the UK, including five

deaths. All caught the disease abroad and almost all cases

could have been prevented.

Be aware of the fact that adventure travellers

are usually more exposed to malaria than ordinary travellers

due

to the nature of their activities and the fact that they travel

to the more remote locations.

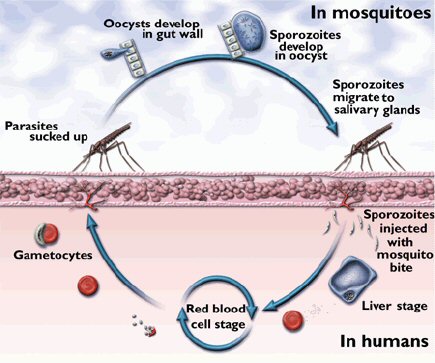

| The

Malaria Cycle (Plasmodium life cycle) |

|

|

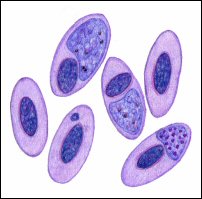

Ruptured

blood cells release free parasites (gametocytes) into

the host's bloodstream.

The human host shows the classic malaria symptoms at

this stage.

The gametocytes are sucked up by a feeding mosquito

and the cycle begins again.

|

The

Prevention and Treatment of Malaria

|

Malaria

is a preventable infection that can be fatal if left

untreated.

You

cannot be vaccinated against malaria (yet), You

cannot be vaccinated against malaria (yet),

but you can protect yourself.

Click

on the image (right) to view a video presentation showing

the dangers of Malaria,

how easily it can spread, and it's effects on humans.

|

| Hope

for a new malaria vaccine |

|

The

world's first malaria vaccine, has received a green

light for future use in babies in sub-Saharan Africa. The

world's first malaria vaccine, has received a green

light for future use in babies in sub-Saharan Africa.

The European Medicines Agency gave the Mosquirix vaccine

a favorable review after 30 years of research by the

Malaria Vaccine Initiative. The drug will now be examined

by the World Health Organization.

Individual countries will also need to give the vaccine

their final approval before it can be administered to

children.

The trials showed the vaccine was most effective in

newborn children between the ages of five and 17 months,

cutting the number of malaria cases by almost a half.

The number of cases in younger babies dropped by 27%.

Mosquirix is aimed at young children because

their immune system is still developing. There is currently

no vaccine available to travellers.

Unlike other vaccines that tackle viruses and bacteria,

Mosquirix has been designed to prevent illness caused

by a parasite. It works by stopping the malaria parasite

maturing and multiplying in the liver, after which it

would normally enter the patient's bloodstream and trigger

the disease symptoms.

The vaccine is given out in three doses one month apart,

with an additional booster dose a year and half later

to maintain protection.

Even though malaria is preventable and treatable, the

mosquito born disease killed 584,000 people in 2013,

with 90% of the deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

Of the victims, 83% were children under the age of five.

The World Health Organization lists malaria as the fifth

biggest killer in sub-Saharan Africa.

The vaccine is not yet licensed in countries where malaria

is endemic.

|

Avoidance of Bites

Mosquitoes cause much inconvenience

because of local reactions to the bites themselves and from

the infections they transmit. Mosquito bites spread other

diseases such as yellow fever, dengue fever and Japanese B

encephalitis.

Mosquitoes

bite at any time of day but the

anopheles bites in the night with most activity at dawn and

dusk. If you are out at night wear long-sleeved clothing and

long trousers. Mosquitoes

bite at any time of day but the

anopheles bites in the night with most activity at dawn and

dusk. If you are out at night wear long-sleeved clothing and

long trousers.

Mosquitoes

may bite through thin clothing,

so spray an insecticide or repellent on them. Insect repellents

should also be used on exposed skin.

Spraying insecticides in

the room, burning pyrethroid coils and heating insecticide

impregnated tablets all help to control mosquitoes. If you

are sleeping in an unscreened room a mosquito net (which should

be impregnated with insecticide) is a sensible precaution.

If sleeping out of doors it is essential. Portable, lightweight

nets are available.

NOTE: Things like Garlic, Vitamin B and ultrasound

devices do not prevent mosquito bites.

Taking Anti-Malaria Tablets

It

should be noted that no prophylactic

regimen is 100% effective and advice on malaria prophylaxis

changes frequently. There are currently five prophylactic

regimens used (A,B,C,D & E), due to the differing resistance

that exists by the malaria parasites to the various drugs

used. (See the above map of Malaria Endemic Areas). It

should be noted that no prophylactic

regimen is 100% effective and advice on malaria prophylaxis

changes frequently. There are currently five prophylactic

regimens used (A,B,C,D & E), due to the differing resistance

that exists by the malaria parasites to the various drugs

used. (See the above map of Malaria Endemic Areas).

The tablets you require

depend on the country to which you are travelling (see the

table page). Start taking the tablets before travel take them

absolutely regularly during your stay, preferably with or

after a meal and continue to take them after you have returned.

This is extremely important to cover the incubation period

of the disease.

Prompt Treatment

If you

develop a fever between one week after first exposure

and up to two years after your return, you should seek medical

attention and inform the doctor that you have been in a malarious

area.

Anyone

with suspected malaria should be treated under medical

supervision as soon as possible. If malaria is diagnosed then

treatment is a matter of urgency. Treatment should not normally

be carried out by unqualified persons. Anyone

with suspected malaria should be treated under medical

supervision as soon as possible. If malaria is diagnosed then

treatment is a matter of urgency. Treatment should not normally

be carried out by unqualified persons.

The drug treatment of malaria depends on the type and

severity of the attack. Typically, Quinine Sulphate tablets

are used and the normal adult dosage is 600mg every twelve

hours which can also be given by intravenous infusion if the

illness is severe.

Remember: Prevention

is better than cure and over two million people die from malaria

every year. It is a very serious illness!

Side Effects of Anti-Malarials

Like all medicines,

anti-malarials can sometimes cause side-effects:

Proguanil (Paludrine)

can cause nausea and simple mouth ulcers.

Chloroquine (Nivaquine

or Avloclor) can cause nausea, temporary blurred vision and

rashes.

Patients

with a history of psychiatric disturbances (including

depression) should not take mefloquine as it may precipitate

these conditions. It is now advised that mefloquine be started

two and a half weeks before travel. Patients

with a history of psychiatric disturbances (including

depression) should not take mefloquine as it may precipitate

these conditions. It is now advised that mefloquine be started

two and a half weeks before travel.

Doxycycline does carry

some risk of photosensitisation i.e. can make you prone to

sunburn.

Malarone is a relatively

new treatment and is virtually free of side effects. It is

licensed for use in stays of up to 28 days but there is now

experience of it being taken safely for up to three months.

No other tablets

are required with mefloquine or doxycycline or Malarone.

Drug

Resistance Drug

Resistance

It is the plasmodia that cause malaria that develop resistance

to anti-malarial drugs not the mosquitoes that transmit the

disease.

Resistance to antimalarial drugs is proving to be a challenging

problem in malaria control in most parts of the world. Since

the early 60s the sensitivity of the parasites to chloroquine,

the best and most widely used drug for treating malaria, has

been on the decline.

Drug resistance is the ability of a parasite species to survive

and multiply despite the administration of a drug in doses

equal to or higher than those usually recommended but within

the limit of tolerance.

Newer

antimalarials have been developed in an effort to tackle this

problem, but all these drugs are either expensive or have

undesirable side effects. Newer

antimalarials have been developed in an effort to tackle this

problem, but all these drugs are either expensive or have

undesirable side effects.

The discovery of chloroquine revolutionalised the treatment

of malaria, pushing quinine to the sidelines.

However, after a variable length of time, the parasites, especially

the falciparum species, have started showing resistance to

these new drugs.

Resistance is most commonly seen in P. falciparum whereas

only sporadic cases of resistance have been reported in P.

vivax malaria.

Resistance to chloroquine is most prevalent, while resistance

to most other antimalarials has also been reported.

Resistance to chloroquine began from two epi-centres; Colombia

(South America) and Thailand (South East Asia) in the early

1960s. Since then, resistance has been spreading world wide.

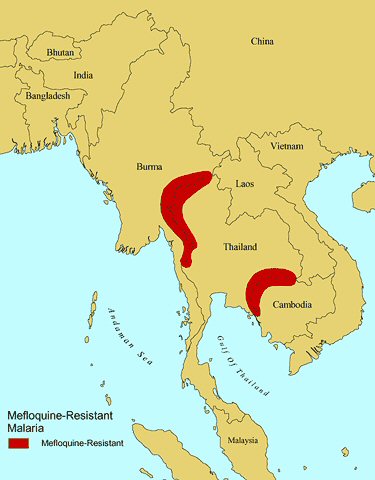

Recently, cases of mefloquine

resistance have been reported from areas of Thailand bordering

with Burma and Cambodia (see map left). Travellers to Thailand

are therefore advised to avoid using mefloquine when travelling

to these risk areas.

Because

mefloquine is structurally similar to chloroquine, cross resistance

is possible Because

mefloquine is structurally similar to chloroquine, cross resistance

is possible

due to the prolonged half life of mefloquine.

Further

in-depth information about the malaria risk to travellers

can be obtained from the following documents (pdf format):-

|

The information supplied

here is derived from a number of reliable sources

and is compared and compiled into the alphabetical lists

found on this web site.

Countries requiring malaria prophylaxis should be

regarded as being at risk all year round and

you should also assume that the whole country

is at risk unless otherwise indicated. The malaria

regimen is the recommended regimen for a country.

Use of the incorrect regimen may not provide adequate

cover.

When there are two different regimens

for the same country, they are area specific. Read the

text to find out which regimen is suitable for the area

you require.

Where regimen 1 is indicated there is Chloroquine

resistance in that region and it is very likely to be

the Falciparum malaria which is the most serious form

of the disease. In this instance it is vitally important

that travellers take adequate prophylaxis.

Remember:- No prophylaxis is 100% effective

but not taking anti-malarials where they are indicated

will put you at greater risk should you get the disease.

Remember - Malaria is a killer!

|

|

The Different Drug Regimens

|

| Regimen

1 |

Mefloquine one 250mg tablet

weekly. OR

Doxycycline one 100mg capsule daily. OR

Malarone one tablet daily. |

| Regimen

2 |

Chloroquine 300mg

weekly (2x150mg tablets). PLUS

Proguanil 200mg daily (2x100mg tablets). |

| Regimen

3 |

Chloroquine 300mg

weekly (2x150mg tablets) OR

Proguanil 200mg daily (2x100mg tablets).

|

| Regimen

4 |

No

prophylactic tablets required but anti mosquito measures

should be strictly observed: Avoid

mosquito bites by covering up with clothing such as long

sleeves and long trousers especially after sunset, using

insect repellents on exposed skin and, when necessary,

sleeping under a mosquito net. |

| . |

| Proguanil

|

100mg tablets are

supplied as Paludrine Tablets |

| Chloroquine |

150mg tablets are

supplied as Nivaquine or Avloclor Tablets |

| Mefloquine

|

250mg tablets are

supplied as Lariam Tablets |

| Malarone |

is a

combination of Atovaquone 250mg and Proguanil

100mg |

|

Long Term

Use of Anti-Malaria Drugs

|

| Chloroquine |

May be

taken for periods exceeding five years. |

| Paludrine |

May be

taken for periods exceeding five years. |

| Maloprim |

Can be

taken for periods up to one year. |

| Mefloquine |

Can be

taken for periods up to one year. |

| Doxycycline |

Can be

taken for periods up to six months. |

| Malarone |

Can be

used for travel periods up to one year. |

|

Childrens' Dosages:

Calculate

the dose by weight rather than by age if possible

|

|

Age/Weight

|

Chloroquine

(once weekly)

|

Proguanil

(once daily)

|

Mefloquine

(once weekly)

|

Doxycycline

(once daily)

|

Malarone

(once daily)

|

|

0

- 12 weeks

under 6kg

|

1/4

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

3

- 12 months

6 - 10kg

|

1/2

tablet

|

1/2

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

-

|

|

1

- 3 years

10 - 16kg

|

3/4

tablet

|

3/4

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

1

child's

tablet

|

|

4

- 7 years

16 - 25kg

|

1

tablet

|

1

tablet

|

1/2

tablet

|

-

|

1

child's

tablet

|

|

8

- 12 years

25 - 45 Kg

|

11/2

tablets

|

11/2

tablets

|

3/4

tablet

|

-

|

2

child's

tablets

|

|

13

years and over

45kg and over

|

2

tablets

|

2

tablets

|

1

tablet

|

1

capsule

|

1

adult

tablet

|

|

The

above dosages are based upon the guidelines issued by

the Advisory Committee on Malaria Prevention.

|

|

Childrens' Dosages:

Calculate

the dose by weight rather than by age if possible

|

|

Age/Weight

|

Chloroquine

(once weekly)

|

Proguanil

(once daily)

|

Mefloquine

(once weekly)

|

Doxycycline

(once daily)

|

Malarone

(once daily)

|

|

0

- 12 weeks

under 6kg

|

1/4

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

3

- 12 months

6 - 10kg

|

1/2

tablet

|

1/2

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

-

|

|

1

- 3 years

10 - 16kg

|

3/4

tablet

|

3/4

tablet

|

1/4

tablet

|

-

|

1

child's

tablet

|

|

4

- 7 years

16 - 25kg

|

1

tablet

|

1

tablet

|

1/2

tablet

|

-

|

1

child's

tablet

|

|

8

- 12 years

25 - 45 Kg

|

11/2

tablets

|

11/2

tablets

|

3/4

tablet

|

-

|

2

child's

tablets

|

|

13

years and over

45kg and over

|

2

tablets

|

2

tablets

|

1

tablet

|

1

capsule

|

1

adult

tablet

|

|

The

above dosages are based upon the guidelines issued by

the Advisory Committee on Malaria Prevention.

|

|

Adult

Dosages

|

|

Regimen

|

Dose

for

Chemoprophylaxis

|

Usual

amount

per tablet (mg)

|

| Areas

without drug resistance: |

|

Chloroquine

Proguanil

|

2

tablets weekly

2

tablets daily

|

150mg

(base)

100mg

|

| Areas

of little chloroquine resistance (poorly effective where

marked resistance): |

Chloroquine

plus

Proguanil |

2

tablets weekly

2 tablets daily |

150mg

(base)

100mg |

| Areas

of chloroquine resistant P. falciparum: |

|

Mefloquine

Doxycycline

Malarone

(atovaquone & proguanil)

|

1

tablet weekly

1

tablet/capsule daily

1

tablet daily

|

250mg

(228 in USA)

100mg

250mg

atovaquone &

100mg proguanil

|

| Countries

where there is currently no risk of malaria: |

|

|

| Malaria

prophylaxis for Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

| Low

risk |

- Cape

Verde - Remember, low risk if fever develops.

- Mauritius

- Except a few rural areas where chloroquine prophylaxis

is appropriate.

|

Avoid

insect bites. |

|

| Risk

in parts of the country Some chloroquine resistance present.

|

- Botswana

- Only in the northern half of the country - November

to June.

- Mauritania

- All year round in the south. November to June in

the north.

- Zimbabwe

- Areas below 1,200 metres - November to June. All

year long in the Zambezi Valley where Doxycycline,

Mefloquine or Malarone are preferable. Risk is negligible

in Harare and Bulawayo.

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone |

| Risk

very high, or locally very high. Chloroquine resistance

very widespread. |

- Angola

- Benin

- Burkina

Faso

- Burundi

- Cameroon

- Central

African Republic

- Chad

-

Comoros

- Congo

- Djibouti

- Equatorial

Guinea

- Eritrea

|

- Gabon

- Gambia

- Ghana

- Guinea

- Guinea

Bissau

- Ivory

Coast

- Kenya

- Liberia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Mali

- Mozambique

- Niger

- Nigeria

|

- Principe

- Rwanda

- Sao

Tome

- Senegal

- Sierra

Leone

- Somalia

- Sudan

- Swaziland

- Tanzania

- Togo

- Uganda

- Zaire

- Zambia

|

- Ethiopia

- Areas below 2,200 metres. No risk in Addis Ababa

- Namibia

- The northern third of the country - November to

June. All year long around the Kavango and Kunene

rivers.

- South

Africa - North east, low altitude areas of Mpumalanga

and Northern Provinces, Northeast KwaZulu-Natal as

far south as the Tugela river. Risk present in Kruger

National Park.

- Zimbabwe

- The Zambezi Valley.

|

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil - (limited protection)

|

| Malaria

prophylaxis for North Africa, Middle East & South

West Asia |

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

| Risk

very low. |

- Algeria

- Virtually no risk

- Egypt

- Main tourist areas are malaria free.

- Georgia

- Some south eastern villages July to October.

- Kyrgystan

- Some southern and western areas.

- Libya

- Morocco

- A few rural areas only limited risk.

- Turkey

- Most tourist areas.

- Uzbekistan

- Sporadic cases in extreme south east only.

|

Avoid

mosquito bites |

|

| Risk

low |

- Armenia

- The whole country June to October.

- Azerbaijan

- Southern border area June to October.

- Egypt

- El Faiyum region only, June to October.

- Iraq

- Basrah and rural north, May to November.

- Syria

- Northern border, May to October.

- Turkey

The plain around Adana, Side & south east Anatolia,

March to November.

- Turkmenistan

- The south east only, June to October.

|

Chloroquine |

Proguanil |

| Risk

present. Some chloroquine resistance present. |

- Afghanistan

- Areas below 2,000 metres, May to November.

- Iran

- Oman

- Remote rural areas only.

- Saudi

Arabia - The whole country except northern, eastern

and central provinces, Asir plateau, and western border

cities where there is very little risk. No risk in

Mecca.

- Tajikistan

- Southern border areas, June to October.

- Yemen

- No risk in Sana'a city.

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

|

| Malaria

prophylaxis for South Asia (Indian Subcontinent)

|

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

| Very

low risk. |

- Maldives

- no risk

- India

- No risk in parts of mountain states of the north.

|

Avoid

mosquito bites |

|

| Risk

variable. Chloroquine resistance usually moderate. |

- Bangladesh

- The whole country except Chittagong Hill Tracts.

No risk in Dhaka City.

- Bhutan

- Southern districts only.

- India

- All areas below 2,000 metres, including Goa.

- Nepal

- Areas below 1,500 metres, especially Terai districts.

No risk in Kathmandu.

- Pakistan

- Areas below 2,000 metres.

- Sri

Lanka - No risk in Colombo.

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

Will

vary locally. |

Risk

high.

Chloroquine resistance high. |

- Bangladesh

- Chittagong Hill Tract Districts only.

- India

- Assam region.

|

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

| Malaria

prophylaxis for South East Asia |

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

| Risk

very low. Remember malaria is possible if fever develops. |

- Bali

- Part of Indonesia

- China

- Main tourist areas.

- Hong

Kong

- Indonesia

- Jakarta, main cites and tourist resorts including

Java.

- Malaysia

- Most areas including Kuala Lumpur and Penang.

- North

Korea - A few southern areas have limited risk.

- Philippines

- Low risk in main cities, Cebu, Bohol & Catanduanes.

No risk in Manilla.

- South

Korea - Limited risk in the extreme northwest.

- Sarawak

- (Borneo) except deep forest areas.

- Thailand

- Bangkok and main tourist areas including Pattaya,

Phuket, Krabi, Hua Hin, Koh Samui, Kanchanaburi, Damnoen

Sadouak, Ayutthaya, Sukhothai, Khon Kaen & Chiang

Mai.

|

Avoid

mosquito bites |

|

| Risk

variable. Some chloroquine resistance. |

- Indonesia

- Areas other than Bali and low risk cities, or Irian

Jaya and Lombok where the risk is high and chloroquine

resistance is present.

- Philippines

- Rural areas below 600 metres.

- Malaysia

and Sarawak (Borneo) - Deep forest regions of penninsular

Malaysia and Sarawak.

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

Will

vary locally. |

Risk

substantial.

Chloroquine resistance common. |

- Borneo

- Sabah

- Cambodia

- Most of the country except Phnom Penh where there

is no risk.

- China

- Yunnan and Hainan provences only. All other remote

areas use chloroquine.

- East

Timor

- Irian

Jaya & Lombok

- Laos

- except Vientiane where there is no risk.

- Myanmar

- (formerly Burma).

- Sabah

- Part of Malaysia (Borneo)

- Vietnam

- Most rural areas, no risk in cities, Red River delta

area and the coastal plain north of Nha Trang.

|

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone

|

Chloroquine

PLUS

Proguanil |

|

Risk

great.

Chloroquine resistance prevalent. Some

mefloquine resistance reported

|

- Cambodia

- Western provences.

- Thailand

- Near borders with Cambodia & Myanmar. Koh Chang.

- Myanmar

- Eastern part of Shan state.

|

Doxycycline

OR

Malarone |

|

| Malaria

prophylaxis for Oceania |

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

Risk

high.

Chloroquine resistance high. |

- Papua

New Guinea - below 1,800 metres.

- Solomon

Islands

- Vanuatu

|

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone

|

Maloprim

PLUS

Chloroquine |

| Malaria

prophylaxis for South & Central America & the

Caribbean |

|

Risk

|

Country

|

Preferable

regimen

|

Alternative

regimen

|

| Risk

very low |

- Brazil

- Except the Amazon basin region, Mato Grosso &

Maranhao.

|

Avoid

mosquito bites. |

|

| Risk

variable to low, no chloroquine resistance present. |

- Argentina

- Rural areas along northern borders only.

- Belize

- Rural areas except Belize district.

- Costa

Rica - Rural areas below 500m.

- Dominican

Republic

- El

Salvador - Only Santa Ana province in the West.

- Guatamala

- Areas below 1,500 metres.

- Haiti

- The whole country.

- Honduras

- The whole country.

- Mexico

- Some rural areas rarely stayed in by tourists.

- Nicaragua

- The whole country.

- Panama

- West of the canal.

- Paraguay

- Some rural areas.

|

Chloroquine |

Proguanil |

| Risk

variable or high, some chloroquine resistance present.

|

- Bolivia

- Rural areas below 2,500 metres

- Ecuador

- Areas below 1,500 metres. No malaria in Galapagos

Islands nor in Guayaquil.

- Panama

- East of the canal.

- Peru

- Rural areas below 1,500 metres.

- Venezuela

- Rural areas other than the coast. Caracas is free

of malaria.

|

Proguanil

PLUS

Chloroquine |

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone |

Risk

high,

marked chloroquine resistance. |

- Brazil

- Amazon basin region, Mato Grosso & Maranhao

only. Very low risk and no chemoprophylazis required

elsewhere.

- Colombia

- Most areas below 800m

- Ecuador

- Esmeraldas Province.

- French

Guiana - Especially border areas.

- Guyana

- All interior regions.

- Surinam

- Except Paramaribo and coast.

- Amazon

basin areas of Bolivia, Venezuela and Peru.

|

Doxycycline

OR

Mefloquine

OR

Malarone

|

Proguanil

PLUS

Chloroquine |

Treatment

of Malaria with Artemisinin Treatment

of Malaria with Artemisinin

Artemisinin is a powerful antimalarial compound

derived from the sweet wormwood plant (Artemisia Annua) and

has transformed the tratment of malaria

It is a natural plant compound. first isolated in 1972 by

Chinese scientist Professor Youyou Tu and her team from the

Artemisia Annua plant known as 'Qinghao' which has been used

in Chinese herbal medicine for over two millennia to treat

fever.

The sweet wormwood plant, originally

from Asia's temperate regions, particularly China is now grown

worldwide for its medicinal uses.

-

Artemisinin

helps significantly reduce the parasites but doesn't stay

in the body for a long time, being eliminated within hours.

It is usually partnered with another drug that eliminates

the remaining parasites over a longer period of time,

reducing treatment for P. falciparum malaria to 3 days.

-

Artesunate,

an artemisinin derivative, is highly effective at treating

severe malaria as it is the only artemisinin derivative

that can be given via intravenous injection. This allows

it to take immediate effect, clearing parasites rapidly,

an important priority in severely ill patients whose symptoms

can continue to deteriorate quickly.

-

Like

all antimalarials before it, resistance to artemisinin

will continue to grow, as parasites evolve. Strategies

for a better usage of existing ACTs and research into

non-artemisinin treatments are crucial to ensure we can

continue to treat this deadly disease into the future.

Artemisinin

works mainly on the asexual blood stage, and particularly

the young-ring stage, a critical phase in the malaria parasite’s

lifecycle. Artemisinin

works mainly on the asexual blood stage, and particularly

the young-ring stage, a critical phase in the malaria parasite’s

lifecycle.

During this stage, parasites multiply quickly in the bloodstream

by consuming haemoglobin to get proteins for growth therby

increasing their numbers in the blood and causing the symptoms

of malaria.

When artemisinin is given, heme from broken-down hemoglobin

in the blood breaks artemisinin's endoperoxide bond. This

creates highly reactive oxygen particles that attack the malaria

parasites killing them.

The endoperoxide bond (a special chemical structure with a

peroxide group) is crucial for artemisinin's antimalarial

effects. However, we still don't fully understand how it works.

To boost its effectiveness, scientists have developed several

artemisinin derivatives, including dihydroartemisinin, artesunate,

and artemether.

Note:

Artemisinin is currently used to treat malaria rather

than as a prophylactic.

|