|

Typhoid

Fever Typhoid

Fever

Typhoid fever is a life-threatening illness caused by the

bacterium Salmonella Typhi. It belongs to the Salmonella

group which contains nearly 2,000 different types causing

mild diseases such as food poisoning, through to the more

serious disease of typhoid fever. Paratyphoid fever

is a similar but less severe variant.

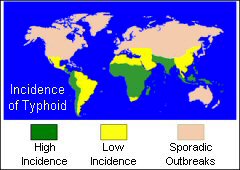

It is a common illness in the developing world, where it affects

about 12.5 million people each year.

Typhoid fever occurs in most parts of the world except in

developed countries such as the United Kingdom, Western Europe,

USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Therefore,

if you are traveling to the developing world, you should consider

taking precautions. Travellers to Asia, Africa, and Latin

America are especially at risk.

The

typhoid fever bacteria is carried in the bloodstream and intestinal

tract of infected persons. A small number of persons, called

carriers, recover from the fever but continue to carry the

bacteria. Both ill persons and carriers shed the bacteria

in their feces. Diagnosis requires medical opinion and examination

of the blood. The

typhoid fever bacteria is carried in the bloodstream and intestinal

tract of infected persons. A small number of persons, called

carriers, recover from the fever but continue to carry the

bacteria. Both ill persons and carriers shed the bacteria

in their feces. Diagnosis requires medical opinion and examination

of the blood.

You can get typhoid fever if you eat food or drink beverages

that have been contaminated by a person who is shedding S.

Typhi or if sewage contaminated with S. Typhi bacteria

gets into the water you use for drinking or washing food.

Therefore, typhoid fever is more common in areas of the world

where handwashing is less frequent and water is likely to

be contaminated with sewage.

The incubation period depends on the quantity of the bacteria

swallowed and can vary from one to three weeks.

Persons with typhoid fever usually have a sustained fever

as high as 39° or 40° C. They will also feel weak, have stomach

pains, headache and loss of appetite. In some cases, patients

have a rash of flat, rose-colored spots.

Treatment:

Typhoid fever is usually treated with antibiotics such as

ampicillin or ciprofloxacin which are very effective but should

ideally be given under medical supervision. Hospital admission

may be more appropriate abroad. Persons treated with antibiotics

usually improve within 2 to 3 days, and deaths rarely occur.

However, relapse is not uncommon and patients may develop

the carrier state after treatment. It is therefore very important

to have your stools examined on your return if you have been

treated for typhoid abroad. Treatment:

Typhoid fever is usually treated with antibiotics such as

ampicillin or ciprofloxacin which are very effective but should

ideally be given under medical supervision. Hospital admission

may be more appropriate abroad. Persons treated with antibiotics

usually improve within 2 to 3 days, and deaths rarely occur.

However, relapse is not uncommon and patients may develop

the carrier state after treatment. It is therefore very important

to have your stools examined on your return if you have been

treated for typhoid abroad.

Without treatment this illness can

be fatal!!. Persons who do not receive treatment

may continue to have the fever for weeks or months, and as

many as 20% may die from complications such as peritonitis

resulting from perforation of the gut wall.

Typhoid

fever can be prevented and can usually be treated with antibiotics.

If you are planning to travel to a region where it exists,

you should know about it and what steps you can take to protect

yourself. Typhoid

fever can be prevented and can usually be treated with antibiotics.

If you are planning to travel to a region where it exists,

you should know about it and what steps you can take to protect

yourself.

There are two basic actions that can help to protect you from

typhoid fever:

1. Get vaccinated against typhoid fever.

2. Avoid risky foods and drinks.

Watching what you eat and drink when you travel is just as

important as being vaccinated. This is because the vaccines

are not completely effective. Avoiding risky foods will also

help protect you from other illnesses, including travelers'

diarrhoea, cholera, dysentery, and hepatitis A.

Tetanus Tetanus

Tetanus is a potentially fatal disease which is caused by

an infection of the bacterium Clostridium Tetani. The

bacteria enter the body through a wound where they grow and

produce a powerful toxin which circulates in the blood and

causes muscular rigidity and painful muscle contractions.

Death is usually caused by respiratory problems and exhaustion.

Tetanus

spores are present in soil worldwide and may be introduced

into the body during injury through a puncture wound, burn

or trivial, unnoticed wounds. Tetanus

spores are present in soil worldwide and may be introduced

into the body during injury through a puncture wound, burn

or trivial, unnoticed wounds.

Tetanus can be contracted quite easily through a small wound

such as a scratch through which the organism can get into

the body. There have been reported cases of tetanus in which

the patient cannot even remember the injury since it was so

small and insignificant.

While

vaccination has largely diminished the incidence of tetanus,

the disease has not disappeared. While

vaccination has largely diminished the incidence of tetanus,

the disease has not disappeared.

If individuals are not fully immunised there is always the

risk of tetanus developing in wounds contaminated by soil.

The incubation period is between four and twenty one days,

commonly around ten days.

The first sign of tetanus is when the patient may notice jaw

stiffness and difficulty in opening the mouth (lock jaw).

Treatment: Requires medical supervision in hospital.

Prevention: All wounds, even minor ones should be thoroughly

washed with clean water and soap taking particular care to

remove all dirt and loose tissue.

Immunisation

against tetanus is highly protective and adults and children

should ensure they are in date for it. Booster doses should

be given at ten year intervals. Immunisation

against tetanus is highly protective and adults and children

should ensure they are in date for it. Booster doses should

be given at ten year intervals.

Booster doses in addition to five doses are not recommended

except in the case of the treatment of a tetanus-prone wound.

The Department of Health advised in 2002 that tetanus vaccine

is to be replaced by the combined tetanus/low dose diphtheria

vaccine for adults and adolescents for routine use and for

travel vaccination. Stocks of single tetanus vaccine are now

exhausted and companies are no longer supplying this product.

Poliomyelitis

(polio) Poliomyelitis

(polio)

Poliomyelitis, normally referred to as polio is caused by

a virus which is spread from person-to-person primarily through

faecal contamination of food and water although it can also

be spread by droplet transfer.

Initially, infection of the gut can spread to the spinal cord

or brain where it can cause paralysis. In the days before

widespread vaccination it tended to occur in epidemics.

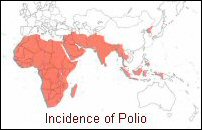

Travellers

who have not been immunised or whose immunity has waned are

at risk if they are travelling to areas of the world where

polio still occurs. ie. Nigeria, Niger, India, Pakistan and

Afghanistan are particularly high risk. Travellers

who have not been immunised or whose immunity has waned are

at risk if they are travelling to areas of the world where

polio still occurs. ie. Nigeria, Niger, India, Pakistan and

Afghanistan are particularly high risk.

In many cases infection with the polio virus is asymptomatic.

When symptoms do occur, the onset of polio is sudden with

fever, headache, nausea and vomiting as the virus multiplies

in the gut. The virus then invades the blood stream and nervous

system.

Paralysis occurs in less than 1 in 100 cases of infection.

This risk increases with age. The patient may die if the respiratory

and swallowing muscles are affected. Those who survive may

develop residual paralysis. Severe pain, and wasting are common

in paralysed muscles. Recovery can take up to a year.

The incubation period is 7-14 days. A blood test for antibodies

will confirm the diagnosis, although this is not always available

abroad. Patients are infectious by close contact and should

be isolated for at least a week.

Treatment: The development of paralysis is clearly

an emergency and medical help should be sought without delay.

If the paralysis affects the breathing muscles, artificial

means of respiration may be required. Extreme care should

be taken when disposing of excreta for up to 6 weeks.

Prevention: There is an effective vaccine available.

Ten yearly boosters should be given to ensure maximum immunity

and travellers should ensure they are in date for polio immunisation.

Past

infection with polio does not always give complete protection

as there are three strains of the virus. Past

infection with polio does not always give complete protection

as there are three strains of the virus.

As the disease is usually spread through close contact, try

to avoid crowded places in high risk areas as much as possible.

(buses, trains,public swimming pools). This could prove difficult

in some countries such as India. Therefore vaccination would

be imperative if travelling there.

The World Health Organisation is making great efforts to encourage

widespread use of polio vaccine in an attempt to eradicate

polio from all the countries of the world. Many countries

have already been certified polio free by the WHO. By 1994,

the Americas were certified as polio-free.

Hepatitis

A Hepatitis

A

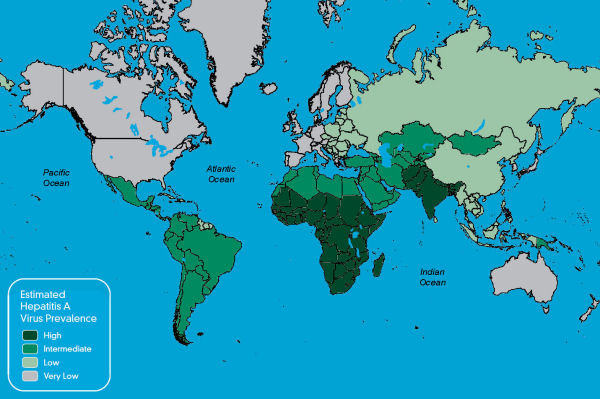

This is a viral disease that causes inflammation of the liver.

It occurs worldwide and is especially prevalent in areas of

poor sanitation and hygiene.

Many children in developing countries are infected with the

virus at an early age, usually without symptoms. Past infection

with hepatitis A virus gives life long immunity.

However, in the developed world where sanitation is better,

fewer people are contracting the disease during childhood

and are therefore at risk when they become adults from the

more severe form of the disease, which they could catch when

they travel to areas of the world where hepatitis A is more

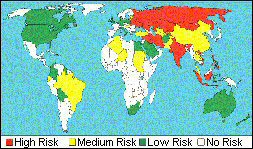

common. The map below shows the global incidence of Hepatitis

A.

The virus

is transmitted from person-to-person by the faecal-oral route

particularly in areas with poor sanitation and overcrowding.

It is quickly spread through close contact, particularly within

families and institutions and is commonly associated with

eating and drinking contaminated food and water. Food outbreaks

are often linked to raw or undercooked shellfish and raw vegetables

although almost any food can be implicated which has been

poorly cooked in sewage-polluted water.

Hepatitis

A has a wide range of symptoms, from an infection without

any noticeable symptoms through to jaundice, liver failure

and death. Unlike hepatitis B, there is no chronic carrier

state for hepatitis A. Hepatitis

A has a wide range of symptoms, from an infection without

any noticeable symptoms through to jaundice, liver failure

and death. Unlike hepatitis B, there is no chronic carrier

state for hepatitis A.

Symptoms include fever, chills, weakness, loss of appetite,

nausea and abdominal discomfort, followed within a few days

by jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes). The urine becomes

dark and the stools pale. Jaundice may be severe and prolonged

and complete liver failure may occur.

Prevention: Avoid contaminated food and water.

Hepatitis A can be prevented by vaccination. The immunisation

schedule consists of a single dose of vaccine followed by

a booster dose six to twelve months after the first dose to

give immunity up to ten years.

Cholera Cholera

Cholera is a bacterial infection of the gastro-intestinal

tract caused by the bacterium Vibrio Cholerae.

These bacteria are typically ingested by drinking water

contaminated by improper sanitation or by eating improperly

cooked fish, especially shell fish.

About one million Vibrio cholerae bacteria must be ingested

to cause cholera in normally healthy adults, although increased

susceptibility may be observed in those with weakened immune

systems, individuals with decreased gastric acidity (as from

the use of antacids etc.), or those who are malnourished.

The incubation period is usually two to three days but may

only be a few hours.

Symptoms range from the mild to the severe which may be

fatal and include; diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, nausea,

vomiting, and dehydration.

Vibrio

cholerae causes the disease by producing a toxin that induces

severe painless watery diarrhoea of sudden onset, occasionally

accompanied by vomiting, which rapidly leads to dehydration.

The profuse diarrhoea allows the bacterium to spread

to other people under insanitary conditions. Vibrio

cholerae causes the disease by producing a toxin that induces

severe painless watery diarrhoea of sudden onset, occasionally

accompanied by vomiting, which rapidly leads to dehydration.

The profuse diarrhoea allows the bacterium to spread

to other people under insanitary conditions.

The bacteria are transmitted in water or food contaminated

with infected faeces and the disease can occur in large-scale

epidemics where sanitary conditions have broken down such

as those in areas of natural disasters.

Cholera is rare amongst travellers as they tend to avoid the

insanitary conditions which would put them at risk.

Treatment: Medical help should be sought without delay.

Cholera is treated with rehydration and antibiotics, but in

severe cases, can lead to death.

Fluid replacement is essential and should be started as soon

as symptoms occur. The patient should aim to drink as much

non-alcoholic fluid as it takes to maintain a good output

of normal looking urine (this may be as much as six or seven

litres a day).

Prevention: Avoid contaminated food and water, especially

raw or undercooked seafood from polluted water.

There is a new vaccine (Dukoral) for immunisation against

cholera for people travelling to highly endemic or epidemic

areas, particularly emergency relief and health workers in

refugee situations. The vaccine may be considered for the

following:

- People

working in areas where there are known cholera outbreaks

(e.g. aid workers).

- Travellers

staying for long periods in known high risk areas and/or

where close contact with locals is likely, and who do

not have access to medical care.

- Travellers

to risk areas who have an underlying gastro-intestinal

disease or immune suppression.

The vaccine

is taken as a raspberry flavoured drink and can be used in

adults and children over 2 years.

It is not currently licensed in the UK for travellers diarrhoea.

Meningitis

(Meningococcal) Meningitis

(Meningococcal)

Meningitis

is an infection that causes inflamation of the membranes and

fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. It can be

caused by a viral or bacterial infection.

Viral meningitis is generally less severe and resolves without

specific treatment, while bacterial meningitis (meningococcal)

can be quite severe and may result in brain damage, coma or

even death.

It

can occur in epidemics, especially where large crowds are

gathered, as it is acquired through direct contact or inhalation

of bacteria in droplets coughed or sneezed into the air. It

can occur in epidemics, especially where large crowds are

gathered, as it is acquired through direct contact or inhalation

of bacteria in droplets coughed or sneezed into the air.

Early diagnosis and treatment are very important. If symptoms

occur, the patient should seek medical help immediately. Medical

supervision is required since large doses of antibiotics are

employed. Treatment should be started without delay. Identification

of the type of bacteria responsible is helpful for the selection

of correct antibiotics.

High fever, headache, and stiff neck and a blotchy rash are

common symptoms. These can develop over several hours, or

they may take 1 to 2 days. Other symptoms may include nausea,

vomiting, discomfort with bright lights, confusion, and sleepiness.

As the disease progresses, patients may develop seizures before

going into a coma.

Sporadic

cases of meningitis are found worldwide. In temperate zones,

most cases occur in the winter months. Localized outbreaks

occur in enclosed crowded spaces (e.g. dormitories, military

barracks). In sub-Saharan Africa, in a zone stretching across

the continent from Senegal to Ethiopia (known as the African

“meningitis belt”), large outbreaks and epidemics take place

during the dry season (November–June). Sporadic

cases of meningitis are found worldwide. In temperate zones,

most cases occur in the winter months. Localized outbreaks

occur in enclosed crowded spaces (e.g. dormitories, military

barracks). In sub-Saharan Africa, in a zone stretching across

the continent from Senegal to Ethiopia (known as the African

“meningitis belt”), large outbreaks and epidemics take place

during the dry season (November–June).

Bacterial

meningitis is contagious. The bacteria are spread by direct

person to person contact including aerosol transmission and

exchange of respiratory and throat secretions (i.e. sneezing,

coughing, kissing, etc.).

Fortunately, none of the bacteria that cause meningitis are

as contagious as the viruses that spread the common cold or

influenza, and they are not spread by casual contact or by

simply breathing the air where a person with meningitis has

been.

The

risk to travellers is generally low. However, the risk is

considerable if travellers are in crowded conditions or taking

part in large population movements such as pilgrimages eg.

the Haj to Mecca. Localized outbreaks occasionally occur among

travellers (usually young adults) in camps or dormitories.

Backpackers who use crowded hostels will be at greater risk

during an outbreak The

risk to travellers is generally low. However, the risk is

considerable if travellers are in crowded conditions or taking

part in large population movements such as pilgrimages eg.

the Haj to Mecca. Localized outbreaks occasionally occur among

travellers (usually young adults) in camps or dormitories.

Backpackers who use crowded hostels will be at greater risk

during an outbreak

Prevention:

Avoid overcrowded places and close contact with the local

population.

There are two vaccines used to protect travellers. The meningitis

A + C vaccine and the meningitis ACWY vaccine. The latter

is required for pilgrims and seasonal workers visiting Saudi

Arabia.

Effective treatment is undertaken with a number of antibiotics.

It is important, however, that treatment be started early

in the course of the disease. This will reduce the risk of

mortality to below 15%, although the risk is higher among

the elderly.

Diphtheria Diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by a bacterium called Corynebacterium

diphtheriae that causes a moderately sore throat. Sometimes

the lining of the throat may swell to form "a false membrane"

which can cause difficulties in breathing.

In its early stages, diphtheria may be mistaken for a severe

sore throat. In severe cases the neck tissue may become very

swollen and in tropical countries the infection can occur

in skin ulcers.

It is mainly spread by droplets expelled from the nose and

mouth usually by breathing in diphtheria bacteria after an

infected person has coughed, sneezed or even laughed. It can

also be spread by handling used tissues or by drinking from

a glass used by an infected person.

Nearly

one out of every ten people who get diphtheria will die from

it. Most cases occur among unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated

people. Nearly

one out of every ten people who get diphtheria will die from

it. Most cases occur among unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated

people.

The bacterium produces a toxin which can seriously damage

the heart muscle and the nervous system.

After two to six weeks, the effects of the toxin produced

by the bacteria become apparent with severe muscle weakness,

mainly affecting the muscles of the head and neck. Inflammation

of the heart muscle can cause heart failure.

Death usually occurs either from respiratory failure, heart

failure or a build up of toxin in the nervous system.

Whether

or not the patient dies depends on the severity of the illness,

their level of immunity and the speed with which treatment

is started. Whether

or not the patient dies depends on the severity of the illness,

their level of immunity and the speed with which treatment

is started.

One of the regions where diphtheria is present is eastern

Europe, including Russia and the former states of the Soviet

Union. Cases of have occurred in Finland, Estonia, Poland

and Belarus and even Germany, Belgium and the UK resulting

from imported infection.

Treatment: This is specialised and requires medical

supervision in hospital.

Prevention:

Try to avoid too close contact with people in crowded

places when travelling in endemic regions (particularly kissing

and sharing bottles or glasses). Prevention:

Try to avoid too close contact with people in crowded

places when travelling in endemic regions (particularly kissing

and sharing bottles or glasses).

Diphtheria can be prevented with a safe and effective vaccine.

A vaccine is now available for travellers to provide protection

against both diphtheria and tetanus.

Immunisation is very effective and UK children are immunised

within their first year. Boosters are required every 10 years

for travellers and those at risk.

Rabies Rabies

This is a viral infection that is acquired from the saliva

of an infected or rabid animal, usually a dog or cat. In most

cases infection results from a bite but even a lick on an

open cut or sore may be enough.

Symptoms start with itching and tingling at the site of the

healed bite and then rapidly progresses to include headache,

fever, spreading paralysis, confusion, aggression and hydrophobia

(fear of water).

It may take many weeks or months for symptoms to develop although

it is usually two to eight weeks. Animals may be infectious

for five days before they develop symptoms.

Treatment: Thoroughly cleanse all bites with soap and

water and do not allow the wound to be stitched. Limited bleeding

should be encouraged. Apply alcohol if possible.

If

available human immunoglobulin (HRIG) should be given especially

for bites to the head/face. The disease can almost always

be prevented, even after exposure, if the vaccine is administered

without delay. If

available human immunoglobulin (HRIG) should be given especially

for bites to the head/face. The disease can almost always

be prevented, even after exposure, if the vaccine is administered

without delay.

You should therefore seek medical advice immediately and have

a course of 5 injections of Purified Chick Embryo Cell Vaccine

(PCEC) or Human Diploid Cell Vaccine (HDCV). This can be difficult

to obtain abroad and if necessary the British Embassy or consulate

should be contacted for a supply.

If you have had a pre-exposure course of vaccine you should

still have a 'booster' course of 2 doses of vaccine without

delay.

Prevention: Never approach or handle animals you don't

know, particularly if they are acting strangely.

Pre-exposure immunisation against rabies is recommended for

long-stay travellers/residents and those who intend to travel

to rural and remote areas.

In the event of a bite, your body's responses could be quickly

activated by booster doses of vaccine. There are rarely any

side effects or discomfort from the new type of vaccine unlike

the old types.

Tuberculosis

(TB) Tuberculosis

(TB)

Tuberculosis

(TB) is an airborne, infectious disease caused by a bacterium

called Mycobacterium tuberculosis which primarily affects

the lungs.

While both preventable and curable, TB remains one of the

world’s major causes of illness and death.

Approximately one-third of the world’s population carry

the TB bacteria, almost 9 million of whom develop “active”

TB each year, which can then be spread to others.

The disease is usually spread through infected sputum but

there is a form spread through milk from infected cows.

Transmission

is usually spread by inhalatation of microscopic droplets

that come from a person infected with TB. When coughing, speaking

or sneezing, small droplets are expelled into the air which

quickly dry out but the bacteria can remain airborne for hours. Transmission

is usually spread by inhalatation of microscopic droplets

that come from a person infected with TB. When coughing, speaking

or sneezing, small droplets are expelled into the air which

quickly dry out but the bacteria can remain airborne for hours.

After the tuberculosis bacteria have been inhaled, they invade

the lungs, and within approximately six weeks a small infection

appears which rarely gives any symptoms but sometimes general

malaise, weakness and weight loss are characteristic during

the incubation period which may be up to twelve weeks. After

this, the bacteria can then spread through the blood.

The infection remains dormant in most cases in people who

are otherwise healthy and does not do any obvious harm. Months

or even years later, however, the disease can become reactivated

in different organs if the immune system is weakened. The

lungs are the favourite place for the illness to strike.

Typical symptoms of TB include:

- Having

a persistent cough for more than three weeks that brings

up phlegm, which may be bloody.

- High

temperature (fever).

- Weight

loss.

- Loss

of appetite

- Night

sweats.

- Tiredness

and fatigue.

TB usually

develops slowly and symptoms might not begin until months

or even years after initial exposure to the bacteria.

In

some cases the bacteria infect the body but don't cause any

symptoms, which is known as latent TB. If the bacteria do

cause symptoms it is active TB. In

some cases the bacteria infect the body but don't cause any

symptoms, which is known as latent TB. If the bacteria do

cause symptoms it is active TB.

You should see a GP if you have a cough that lasts more than

three weeks or if you cough up blood or have any of the above

symptoms and have been in contact with someone who has the

disease.

The

bacteria can spread to the blood in individuals who have weak

immune systems (especially when caused by alcohol or HIV).

TB is primarily a disease of the lungs. However, the infection

can spread via blood from the lungs to other organs in the

body, the bones, the urinary tract and sexual organs, the

intestines and even in the skin. Lymph nodes in the lungs

and throat can also get infected.

Sometimes

the disease can be overwhelming; producing meningitis and

coma; this particularly dangerous form is usually found in

children and those who have not previously been vaccinated

or exposed to the disease. Sometimes

the disease can be overwhelming; producing meningitis and

coma; this particularly dangerous form is usually found in

children and those who have not previously been vaccinated

or exposed to the disease.

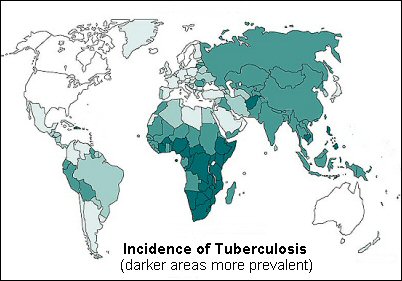

TB is found in every country in the world, but the majority

of TB cases are concentrated in developing countries, particularly

those in Asia and Africa. It is a serious condition but can

be cured with proper treatment.

Three million deaths occur each year from TB, which is more

than any other single infectious disease. The disease is more

common in areas of the world where poverty, malnutrition,

poor general health and social disruption are present. The

disease has been commonly found in places of crowding such

as hostels and prisons where healthcare is poor.

Treatment:

Treatment with antibiotics is effective but is prolonged. Treatment:

Treatment with antibiotics is effective but is prolonged.

Effective and affordable antimicrobial drugs to treat TB disease

have been available for decades but these must be taken for

six to eight months under medical supervision because if treatment

is not completed, the emergence of drug-resistant strains

of the TB bacteria may be encouraged. These medicines may

not always available abroad.

With treatment, a TB infection can usually be cured. Several

different antibiotics are used. This is because some forms

of TB are resistant to certain antibiotics. If you are infected

with a drug-resistant form of TB, treatment can last as long

as 18 months.

The usual course of treatment is:

- Two

antibiotics – isoniazid and rifampicin – every

day for six months.

- Two

additional antibiotics – pyrazinamide and ethambutol

– every day for the first two months.

After

taking the medicine for two weeks, most people are no longer

infectious and feel much better. However, it is important

to continue taking the medicine exactly as prescribed and

to complete the whole course of antibiotics. After

taking the medicine for two weeks, most people are no longer

infectious and feel much better. However, it is important

to continue taking the medicine exactly as prescribed and

to complete the whole course of antibiotics.

It may be several weeks or months before a person starts to

feel better. The exact length of time will depend on your

overall health and the severity of your TB.

If you have been in close contact with someone who has TB,

tests may be carried out to see if you are also infected.

These can include a chest X-ray, sputum tests, blood tests

and a skin test.

Prevention:

Travelers should try to avoid exposure to TB patients in crowded

environments (such as hospitals, prisons, or homeless shelters).

Avoid other overcrowded places, particularly where spitting

is common.

The risk of TB transmission on an aeroplane does not appear

to be higher than in any other enclosed space.

To prevent TB transmission, people who have infectious TB

should not travel by commercial aircraft or other commercial

conveyances.

Never drink unpasteurised milk. If in doubt, boil it before

drinking.

There is a vaccination against TB which can give a valuable

degree of protection, particularly in children.

Those who have not received BCG immunisation are advised to

do so and if for travel purposes, at least six weeks before

departure to ensure a protective level of immunity.

Click on this map to see a larger

map

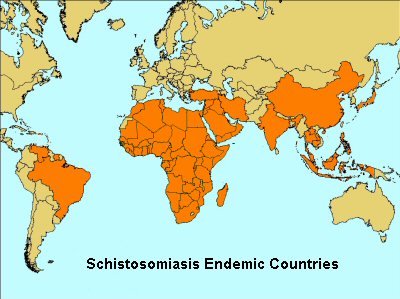

Schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis

Also

known as bilharzia, is a disease caused by parasitic worms

called schistosoma. They belong to the family of flat worms

known as trematodes or flukes. There are several different

species e.g. S. mansoni, S. haematobium, and S. japonicum.

About 200 million people are thought to be infected world-wide.

The infection occurs when the skin comes into contact with

contaminated fresh water which contains a certain type of

snail that carry the schistosomes.

Fresh water becomes contaminated by Schistosoma eggs when

people who are infected urinate or defaecate in the water.

The eggs then hatch, and if the snails are present in the

water, the parasites invade the snails and grow and develop

inside them. The parasites eventually leaves the snails and

enter the water where they can survive for up to 48 hours.

Schistosoma

parasites can penetrate the skin of persons who are wading,

swimming, bathing, or washing in contaminated water. Within

several weeks, worms grow inside the blood vessels of the

body and produce eggs. Some of these eggs travel to the bladder

or intestines and are passed into the urine or stools. Schistosoma

parasites can penetrate the skin of persons who are wading,

swimming, bathing, or washing in contaminated water. Within

several weeks, worms grow inside the blood vessels of the

body and produce eggs. Some of these eggs travel to the bladder

or intestines and are passed into the urine or stools.

Symptoms:

Within days after becoming infected, a rash or itchy skin

may develop. Fever, chills, cough, and muscle aches can begin

within 1-2 months of infection. Most people have no symptoms

at this early phase of infection.

Eggs travel to the liver or pass into the intestine or bladder.

Rarely, eggs are found in the brain or spinal cord and can

cause seizures, paralysis, or spinal cord inflammation. For

people who are repeatedly infected for many years, the parasite

can damage the liver, intestines, lungs, and bladder.

The symptoms of schistosomiasis are caused by the body's reaction

to the eggs, not by the worms themselves.

Anyone

travelling to areas where schistosomiasis occurs and whose

skin comes in contact with fresh water from canals, rivers,

streams, or lakes, is at risk of getting schistosomiasis. Anyone

travelling to areas where schistosomiasis occurs and whose

skin comes in contact with fresh water from canals, rivers,

streams, or lakes, is at risk of getting schistosomiasis.

If someone does develop any of the symptoms after visiting

one or more of the countries where schistosomiasis is found

and was in contact with fresh water, they should go immediately

to their doctor and describe in detail where and for how long

they travelled and that they may have been exposed to contaminated

water.

They will need to provide a stool or urine sample for analysis

to see if you the parasites are present. A blood test has

also been developed but there should be a six to eight week

interval after the last exposure to contaminated water before

the blood sample is taken.

Prevention:

|

- Avoid

swimming or wading in fresh water when you are in

countries in which schistosomiasis occurs. Swimming

in the ocean and in chlorinated swimming pools is

generally thought to be safe.

-

Drink safe water. Because there is no way to make

sure that water coming directly from canals, lakes,

rivers, streams or springs is safe, you should either

boil water for 1 minute or filter the water before

drinking it.

- Boiling

water for at least 1 minute will kill any harmful

parasites, bacteria, or viruses present. Iodine

treatment alone WILL NOT GUARANTEE that water is

safe and free of all parasites

- Bath

water should be heated for 5 minutes at 65 degrees

Celsius. Water held in a storage tank for at least

48 hours should be safe for showering.

- Vigorous

towel drying after an accidental, very brief water

exposure may help to prevent the Schistosoma parasite

from penetrating the skin but you should NOT rely

on vigorous towel drying to prevent schistosomiasis.

- There

is no vaccine available.

|

|

|

Treatment:

A safe and effective treatment of schistosomiasis is available.

Praziquantel is effective against all human schistozomes.

Treatment is usually for one or two days and no serious toxic

effects have been reported. Treatment:

A safe and effective treatment of schistosomiasis is available.

Praziquantel is effective against all human schistozomes.

Treatment is usually for one or two days and no serious toxic

effects have been reported.

Areas

of the world where schistosomiasis occurs:-

Africa: north Africa, southern Africa, sub-Saharan

Africa, Lake Malawi, the Nile River valley in Egypt.

South America: including Brazil, Surinam, Venezuela.

Caribbean: Antigua, Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe,

Martinique, Montserrat, Saint Lucia.

The Middle East: Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria &

Yemen.

Southeast Asia: India, Bagladesh, Central Indonesia,

the Philippines, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam (the Mekong

Delta), Southern China & Japan.

Leptospirosis

(Weil's disease) Leptospirosis

(Weil's disease)

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease

caused by bacteria of the genus Leptospira. It

affects humans and animals and causes

a wide range of symptoms, including high fever, severe headache,

chills, muscle aches, and vomiting, and may include, red eyes,

abdominal pain, diarrhea, or a rash although

some infected persons may have no symptoms at all. If

the disease is not treated, then kidney damage, meningitis

liver failure, respiratory distress and even death may result.

Outbreaks of leptospirosis are usually caused by exposure

to water contaminated with the urine of infected animals.

Many different kinds of animals carry the bacteria such as

cattle, pigs, horses, dogs, rodents, and wild animals.

Humans

become infected through contact with water, food, or soil

containing urine from these infected animals. This may happen

by swallowing contaminated water or through cuts and contact

with broken skin. The disease is not spread from person to

person. Humans

become infected through contact with water, food, or soil

containing urine from these infected animals. This may happen

by swallowing contaminated water or through cuts and contact

with broken skin. The disease is not spread from person to

person.

The incubation period is anything from two days to four weeks.

The illness usually begins abruptly with fever and other symptoms.

Leptospirosis may occur in two phases; after the first phase,

with fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, vomiting, or diarrhoea,

the patient may recover for a time but become ill again.

If a second phase occurs, it is more severe; the person may

have kidney or liver failure or meningitis. This phase is

also called Weil's disease. Diagnosis of Leptospirosis is

confirmed by laboratory testing of a blood or urine sample.

Leptospirosis

occurs worldwide but is most common in temperate or tropical

climates. It is an occupational hazard for many people who

work with animals, such as farmers, sewer workers, veterinarians,

fish workers, dairy farmers, or military personnel. Leptospirosis

occurs worldwide but is most common in temperate or tropical

climates. It is an occupational hazard for many people who

work with animals, such as farmers, sewer workers, veterinarians,

fish workers, dairy farmers, or military personnel.

It is a recreational hazard for campers or those who participate

in outdoor sports in contaminated areas and has been associated

with swimming, wading, and whitewater rafting in contaminated

lakes and rivers.

Leptospirosis can be effectively treated with antibiotics,

such as doxycycline or penicillin, which should be given as

early as possible in the course of the disease. Intravenous

antibiotics may be required for persons with more severe symptoms.

Persons who are thought to have symptoms suggestive of leptospirosis

should seek medical help immediately.

Ebola

Virus, Lassa Fever & Marburg Virus (the really nasty viruses)

Ebola

Virus

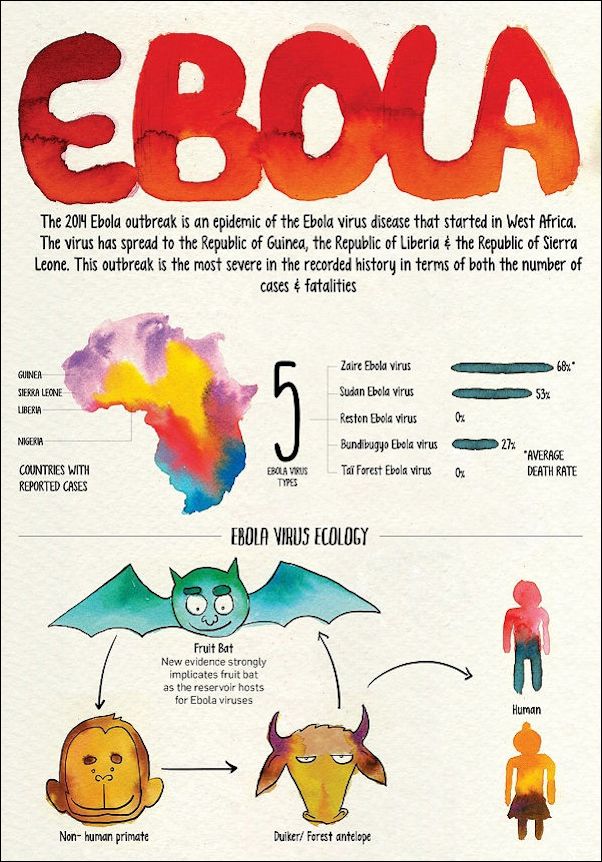

Ebola

Hemorrhagic Fever is a severe, often-fatal disease that

has appeared sporadically since its initial recognition in

1976. Ebola

Hemorrhagic Fever is a severe, often-fatal disease that

has appeared sporadically since its initial recognition in

1976.

The disease is caused by infection with Ebola virus, named

after a river in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in West

Africa, where it was first recognized. The virus is one of

two members of a family of RNA viruses called the Filoviridae.

There are four identified subtypes of Ebola virus. Three of

which have caused disease in humans.

Infections with Ebola virus are acute. There is no carrier

state. Because the natural reservoir of the virus is unknown,

the manner in which the virus first appears in a human at

the start of an outbreak has not been determined. However,

it is thought that the first patient becomes infected through

contact with an infected animal, possibly a primate or a fruit

bat. Infection can occur from ingestion of infected meat.

Most of the previous outbreaks have been caused by meat from

dead infected animals collected by hunters who then sell it

on. Fruit

bats are also widely eaten in rural west Africa – either

smoked, grilled or in a spicy soup.

After

the first patient in an outbreak setting is infected, the

virus can be transmitted in several ways. People can be exposed

to Ebola virus from direct contact with the blood and/or secretions

of an infected person. Thus, the virus is often spread through

families and friends because they come in close contact with

such secretions when caring for infected persons. People can

also be exposed to Ebola virus through contact with objects,

such as needles, that have been contaminated with infected

secretions. Health workers who treat ebola patients are also

at risk and should always wear specialised protective clothing

when treating an infected person.

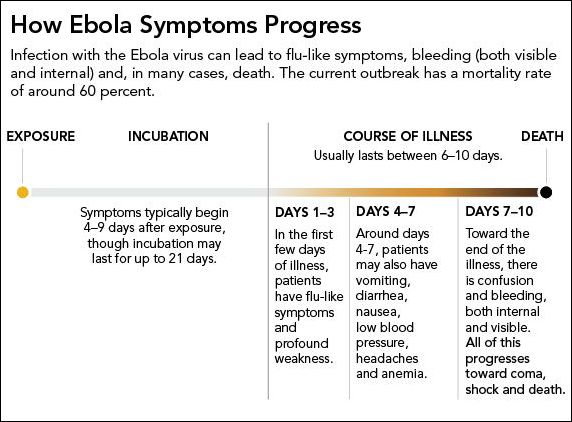

The

incubation period for Ebola HF ranges from 2 to 21 days. The

onset of illness is abrupt and is characterized by fever,

headache, joint and muscle aches, sore throat, and weakness,

followed by diarrhoea, vomiting, and stomach pain. A rash,

decreased kidney and liver functioning, red eyes, hiccups

and internal and external bleeding may be seen in some patients. The

incubation period for Ebola HF ranges from 2 to 21 days. The

onset of illness is abrupt and is characterized by fever,

headache, joint and muscle aches, sore throat, and weakness,

followed by diarrhoea, vomiting, and stomach pain. A rash,

decreased kidney and liver functioning, red eyes, hiccups

and internal and external bleeding may be seen in some patients.

Researchers do not understand why some people are able to

recover from Ebola HF and others are not. However, it is known

that patients who die usually have not developed a significant

immune response to the virus at the time of death.

There is no standard treatment for Ebola HF. Patients must

be isolated and receive supportive therapy. This consists

of balancing the patient’s fluids and electrolytes, maintaining

their oxygen status and blood pressure, and treating them

for any complicating infections.

How

Ebola kills: How

Ebola kills:

Once

the Ebola virus makes its way into the body, it gets into

the body's cells and replicates itself. Then it comes bursting

out of the cells and produces a protein called ebolavirus

glycoprotein that wreaks havoc. The ebolavirus glycoprotein,

attaches to the cells on the inside of blood vessels. This

increases the permeability of the blood vessels leading to

blood leaking out of the vessels. The virus also disrupts

the body's ability to coagulate and thicken the blood. Even

people who don't show hemorrhagic symptoms will experience

this leaking of blood from the vessels which can eventually

lead to shock and, ultimately, death.

The

Ebola virus is also a master of evading the body's natural

defences: It blocks the signaling to cells called neutrophils,

which are white blood cells that are in charge of raising

the alarm for the immune system to come and attack. In fact,

Ebola will infect immune cells and travel in those cells to

other parts of the body, including the liver, kidney, spleen

and brain. The

Ebola virus is also a master of evading the body's natural

defences: It blocks the signaling to cells called neutrophils,

which are white blood cells that are in charge of raising

the alarm for the immune system to come and attack. In fact,

Ebola will infect immune cells and travel in those cells to

other parts of the body, including the liver, kidney, spleen

and brain.

Each time one of the cells is infected with the Ebola virus

and bursts open spilling out its contents, the damage and

presence of the virus particles activates molecules called

cytokines. In a healthy body, these cytokines are responsible

for provoking an inflammatory response so that the body knows

it's being attacked. But in the case of an Ebola patient it

is the overwhelming release of cytokines which cause the flu-like

symptoms that are the first sign of Ebola infection.

The prevention

of Ebola HF in Africa presents many challenges. Because the

identity and location of the natural reservoir of Ebola virus

are unknown, there are few established primary prevention

measures.

The prevention

of Ebola HF in Africa presents many challenges. Because the

identity and location of the natural reservoir of Ebola virus

are unknown, there are few established primary prevention

measures.

There is currently no vaccine that protects against the

Ebola virus.

Education

regarding infection control measures to prevent the spread

of the virus is of paramount importance.

Unless you are travelling to an area where an Ebola outbreak

is occurring and/or you have direct contact with an ill individual

infected with Ebola, the risk of acquiring Ebola virus is

extremely low.

Lassa

fever Lassa

fever

is an acute viral illness that occurs in West Africa.

The illness was discovered in 1969 and named after the town

in Nigeria where the first cases originated. The virus, a

member of the virus family Arenaviridae is animal-borne

and is acquired from a particular kind of wild rodent known

as the multimammate rat.

In the areas of Africa where the disease is endemic, Lassa

fever is a significant cause of mortality. While it is mild

or has no observable symptoms in about 80% of people infected,

the remaining 20% contract a severe multisystem disease. Lassa

fever is also associated with occasional epidemics, during

which the case-fatality rate can reach 50%.

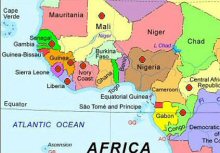

The

disease is known to be endemic (constantly present) in Nigeria,

Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and the Central African Republic,

and there is evidence of infection in nearby countries including

Mali, Senegal, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. However,

because the rodent species which carry the virus are found

throughout West Africa, the actual geographic range of the

disease may extend to other countries in the region. The

disease is known to be endemic (constantly present) in Nigeria,

Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and the Central African Republic,

and there is evidence of infection in nearby countries including

Mali, Senegal, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. However,

because the rodent species which carry the virus are found

throughout West Africa, the actual geographic range of the

disease may extend to other countries in the region.

The virus is shed in the urine and droppings of infected rats

(which are infected for life), and most infections arise through

contact with materials contaminated by these.

Lassa

fever may also spread through person-to-person contact. This

type of transmission occurs when a person comes into contact

with virus in the blood, tissue, secretions, or excretions

of an individual infected with the Lassa virus. Lassa

fever may also spread through person-to-person contact. This

type of transmission occurs when a person comes into contact

with virus in the blood, tissue, secretions, or excretions

of an individual infected with the Lassa virus.

The virus cannot be spread through casual contact (including

skin-to-skin contact without exchange of body fluids). The

virus is present in semen for up to three months after the

disease begins, thus sexual transmission can also occur. It

may also be spread by contaminated medical equipment, such

as reused needles etc.

Marburg

Virus

Marburg haemorrhagic fever is a rare, severe type of haemorrhagic

fever which affects both humans and animals. It is caused

by a genetically unique RNA virus of the filovirus family,

and its recognition led to the creation of this virus family.

The Ebola virus is the only other known member of this family.

Marburg haemorrhagic fever is a rare, severe type of haemorrhagic

fever which affects both humans and animals. It is caused

by a genetically unique RNA virus of the filovirus family,

and its recognition led to the creation of this virus family.

The Ebola virus is the only other known member of this family.

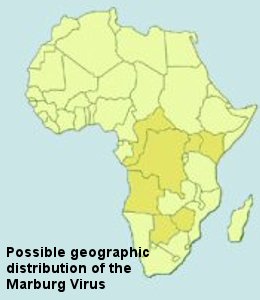

Marburg

virus is indigenous to Africa but the actual geographic area

to which it is native is unknown, but could include parts

of Uganda and Western Kenya, and Zimbabwe. As with Ebola virus,

the actual animal host for Marburg virus also remains a mystery.

Just

how the virus is first transmitted to humans is unknown. However,

as with some other viruses which cause haemorrhagic fever,

humans who become ill with Marburg fever may spread it to

other people.

After

an initial incubation period of five to ten days, the onset

of the disease is sudden and is marked by fever, chills, headache,

and myalgia. Around the fifth day after the onset of symptoms,

a rash appears, most prominent on the chest, back, stomach.

Nausea, vomiting, a sore throat, chest pain, abdominal pain,

and diarrhoea may then appear. Symptoms become increasingly

severe and may include jaundice, inflammation of the pancreas,

severe weight loss, delirium, shock, liver failure, multi-organ

dysfunction and even death.

Because

many of the signs and symptoms of Marburg fever are similar

to those of other diseases, such as malaria or typhoid fever,

diagnosis of the disease can be difficult, especially if only

a single case is involved.

A

specific treatment for this disease is unknown. However, supportive

hospital therapy is required. This includes balancing the

patient's fluids and electrolytes, replacing lost blood and

clotting factors, maintaining their blood pressure, and treating

them for any complicating infections. A

specific treatment for this disease is unknown. However, supportive

hospital therapy is required. This includes balancing the

patient's fluids and electrolytes, replacing lost blood and

clotting factors, maintaining their blood pressure, and treating

them for any complicating infections.

Due to

our limited knowledge of the disease, preventive measures

against transmission from the original animal host have not

yet been established. Measures for prevention of secondary

transmission are similar to those used for other haemorrhagic

fevers.

People

who have close contact with infected humans or animals are

most at risk.

|